[Updated: Wed, Sep 20, 2023 - 17:31:34 ]

The prediction algorithms are classified into two main categories in the machine learning literature: supervised and unsupervised. Supervised algorithms are used when the dataset has an actual outcome of interest to predict (labels), and the goal is to build the “best” model predicting the outcome of interest. On the other side, unsupervised algorithms are used when the dataset doesn’t have an outcome of interest. The goal is typically to identify similar groups of observations (rows of data) or similar groups of variables (columns of data) in data. In this course, we plan to cover several supervised algorithms. Linear regression is one of the most straightforward approaches among supervised algorithms and the easiest to interpret.

Model Description

In most general terms, the linear regression model with \(P\) predictors (\(X_1\),\(X_2\),\(X_3\),…,\(X_p\)) to predict an outcome (\(Y\)) can be written as the following:

\[ Y = \beta_0 + \sum_{p=1}^{P} \beta_pX_{p} + \epsilon.\] In this model, \(Y\) represents the observed value for the outcome of an observation, \(X_{p}\) represents the observed value of the \(p^{th}\) variable for the same observation, and \(\beta_p\) is the associated model parameter for the \(p^{th}\) variable. \(\epsilon\) is the model error (residual) for the observation.

This model includes only the main effects of each predictor and can be easily extended by including quadratic or higher-order polynomial terms for all (or a specific subset of) predictors. For instance, the model below includes all first-order, second-order, and third-order polynomial terms for all predictors.

\[ Y = \beta_0 + \sum_{p=1}^{P} \beta_pX_{p} + \sum_{k=1}^{P} \beta_{k+P}X_{k}^2 + \sum_{m=1}^{P} \beta_{m+2P}X_{m}^3 + \epsilon.\] Sometimes, the effect of predictor variables on the outcome variable is not additive, and the effect of one predictor on the response variable can depend on the levels of another predictor. These non-additive effects are also called interaction effects. The interaction effects can also be a first-order interaction (interaction between two variables, e.g., \(X_1*X_2\)), second-order interaction (\(X_1*X_2*X_3\)), or higher orders. It is also possible to add the interaction effects to the model. For instance, the model below also adds the first-order interactions.

\[ Y = \beta_0 + \sum_{p=1}^{P} \beta_pX_{p} + \sum_{k=1}^{P} \beta_{k+P}X_{k}^2 + \sum_{m=1}^{P} \beta_{m+2P}X_{m}^3 + \sum_{i=1}^{P}\sum_{j=i+1}^{P}\beta_{i,j}X_iX_j + \epsilon.\] If you are uncomfortable or confused with notational representation, below is an example of different models you can write with three predictors (\(X_1,X_2,X_3\)).

A model with only main effects:

\[ Y = \beta_0 + \beta_1X_{1} + \beta_2X_{2} + \beta_3X_{3}+ \epsilon.\]

A model with polynomial terms up to the 3rd degree was added:

\[Y = \beta_0 + \beta_1X_1 + \beta_2X_2 + \beta_3X_3 + \\ \beta_4X_1^2 + \beta_5X_2^2 + \beta_6X_3^2+ \\ \beta_{7}X_1^3 + \beta_{8}X_2^3 + \beta_{9}X_3^3\]

A model with both interaction terms and polynomial terms up to the 3rd degree was added:

\[Y = \beta_0 + \beta_1X_1 + \beta_2X_2 + \beta_3X_3 + \\ \beta_4X_1^2 + \beta_5X_2^2 + \beta_6X_3^2+ \\ \beta_{7}X_1^3 + \beta_{8}X_2^3 + \beta_{9}X_3^3+ \\ \beta_{1,2}X_1X_2+ \beta_{1,3}X_1X_3 + \beta_{2,3}X_2X_3 + \epsilon\]

Model Estimation

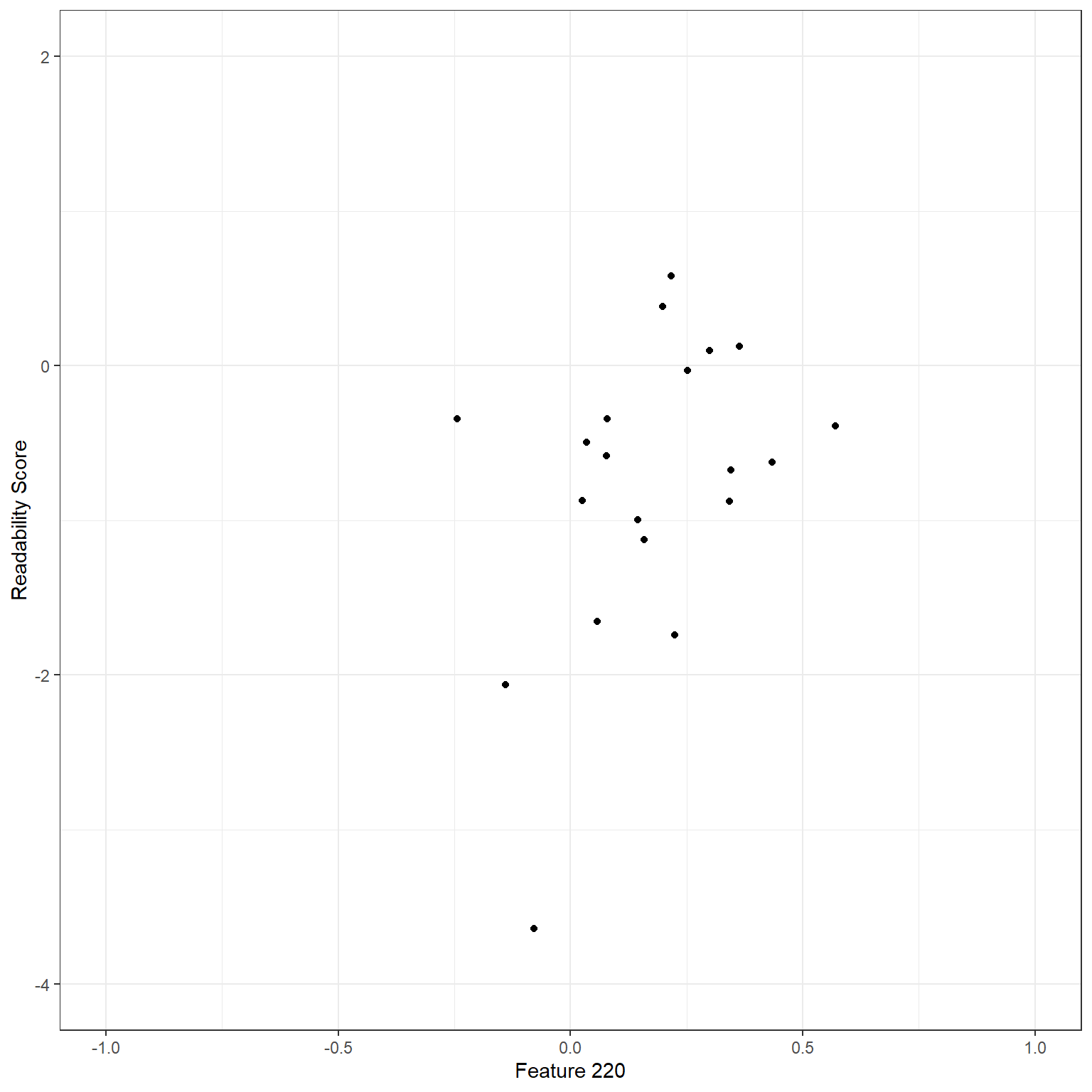

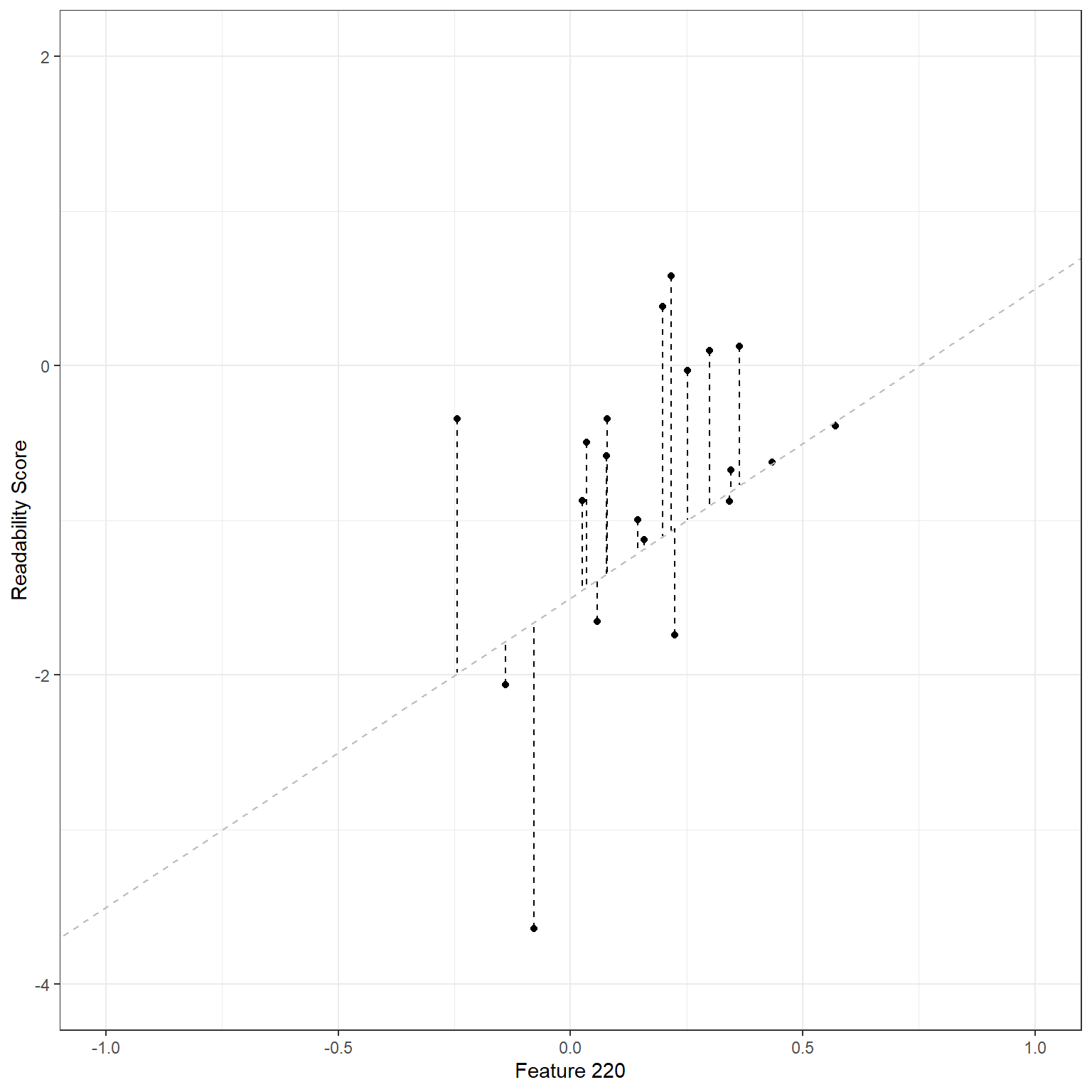

Suppose that we would like to predict the target readability score for a given text from the Feature 220 (there are 768 features extracted from the NLP model as numerical embeddings). Below is a scatterplot to show the relationship between these two variables for a random sample of 20 observations. There seems to be a moderate positive correlation. So, we can tell that the higher the score for Feature 220 is for a given text, the higher the readability score (more challenging to read).

readability_sub <- read.csv('./data/readability_sub.csv',header=TRUE)

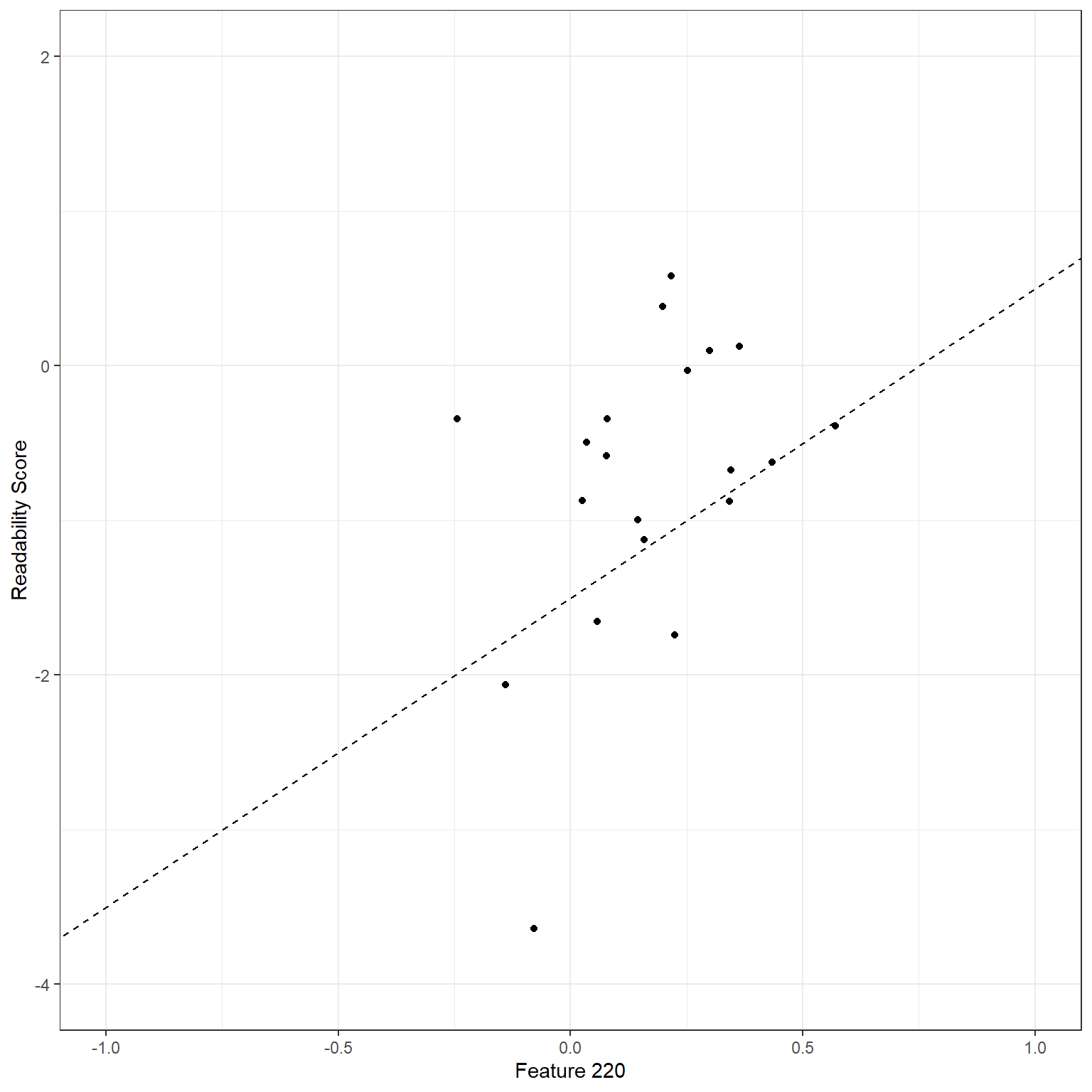

Let’s consider a simple linear regression model: the readability score is the outcome (\(Y\)), and Feature 220 is the predictor(\(X\)). Our regression model would be \[Y = \beta_0 + \beta_1X + \epsilon.\]

In this case, the set of coefficients, {\(\beta_0,\beta_1\)}, represents a linear line. We can write any set of {\(\beta_0,\beta_1\)} coefficients and use it as our model. For instance, suppose I guesstimate that these coefficients are {\(\beta_0,\beta_1\)} = {-1.5,2}. Then, my model would be

\[Y = -1.5 + 2X + \epsilon.\]

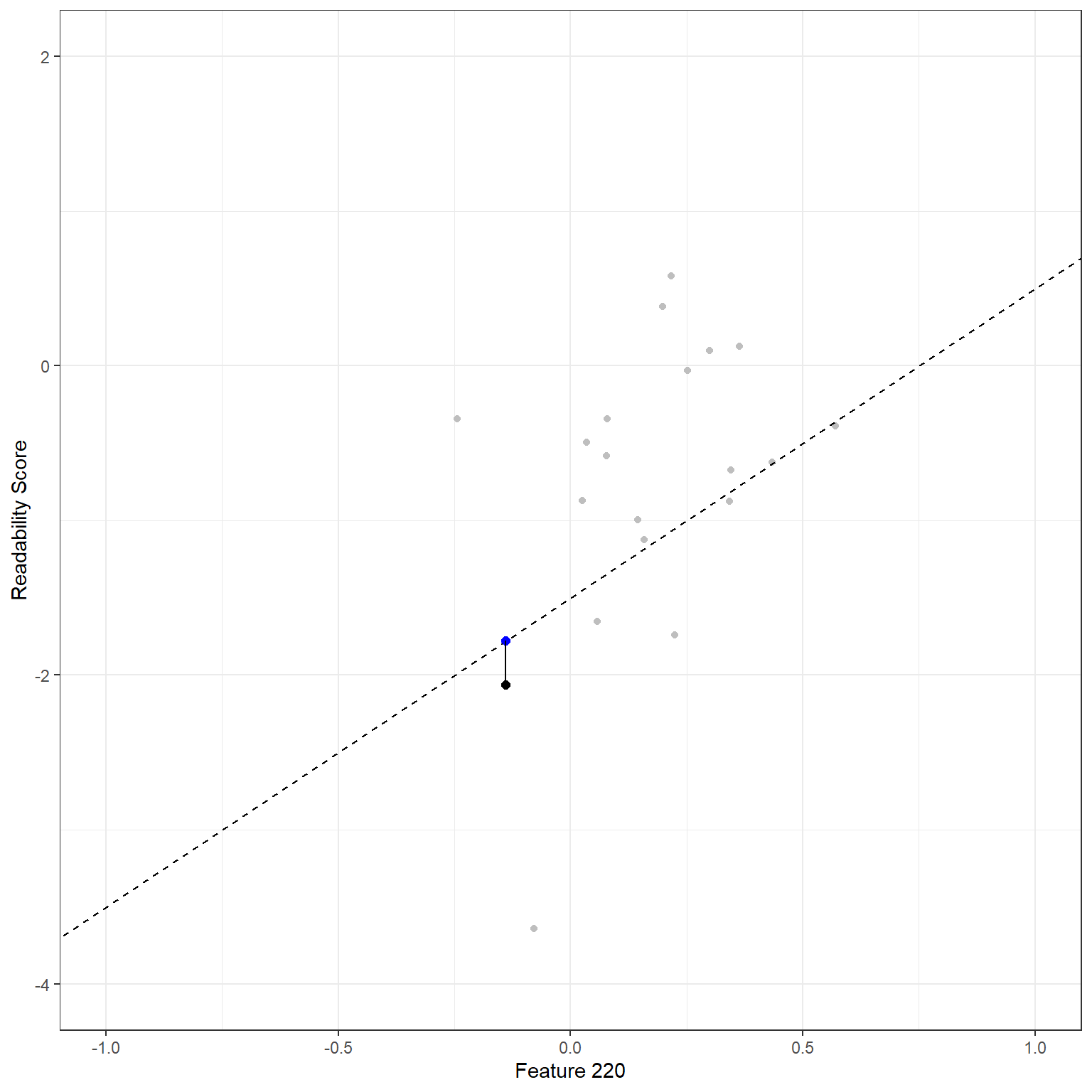

Using this model, I can predict the target readability score for any observation in my dataset. For instance, Feature 220 is -.139 for the first reading passage. Then, my prediction of the readability score based on this model would be -1.778. On the other side, the observed value of the readability score for this observation is -2.062. This discrepancy between the observed value and the model prediction is the model error (residual) for the first observation and captured in the \(\epsilon\) term in the model.

\[Y_{(1)} = -1.5 + 2X_{(1)} + \epsilon_{(1)}.\] \[\hat{Y}_{(1)} = -1.5 + 2*(-0.139) = -1.778\] \[\hat{\epsilon}_{(1)} = -2.062 - (-1.778) = -0.284 \] We can visualize this in the plot. The black dot represents the observed data point, and the blue dot on the line represents the model prediction for a given \(X\) value. The vertical distance between these two data points is this observation’s model error.

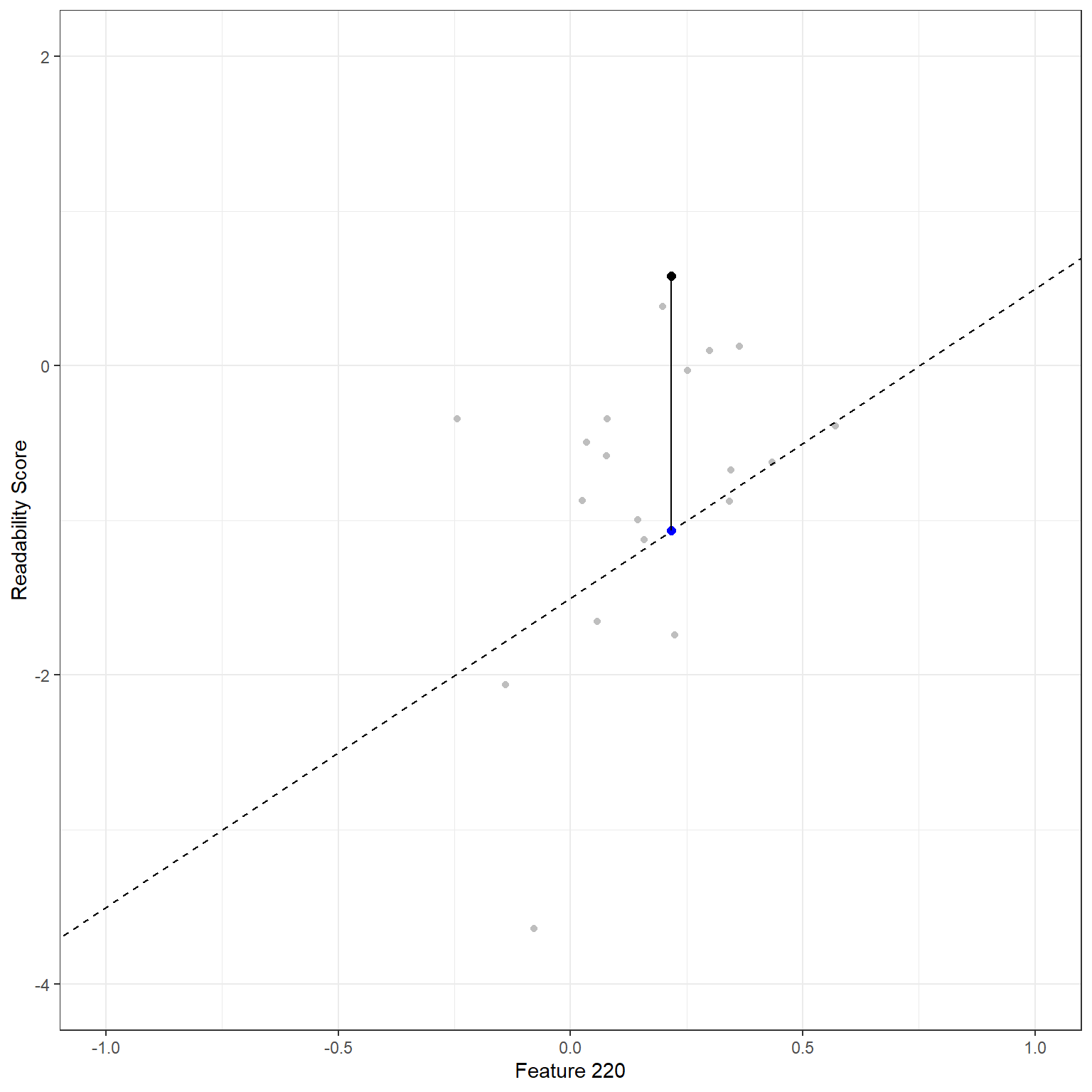

We can do the same thing for the second observation. Feature 220 is equal to 0.218 for the second reading passage. The model predicts a readability score of -1.065. The observed value of the readability score for this observation is 0.583. Therefore the model error for the second observation would be 1.648.

\[Y_{(2)} = -1.5 + 2X_{(2)} + \epsilon_{(2)}.\] \[\hat{Y}_{(2)} = -1.5 + 2*(0.218) = -1.065\] \[\hat{\epsilon}_{(2)} = 0.583 - (-1.065) = 1.648 \]

Using a similar approach, we can calculate the model error for every observation.

d <- readability_sub[,c('V220','target')]

d$predicted <- -1.5 + 2*d$V220

d$error <- d$target - d$predicted

d V220 target predicted error

1 -0.13908258 -2.06282395 -1.7781652 -0.28465879

2 0.21764143 0.58258607 -1.0647171 1.64730321

3 0.05812133 -1.65313060 -1.3837573 -0.26937327

4 0.02526429 -0.87390681 -1.4494714 0.57556460

5 0.22430885 -1.74049148 -1.0513823 -0.68910918

6 -0.07795373 -3.63993555 -1.6559075 -1.98402809

7 0.43400714 -0.62284268 -0.6319857 0.00914304

8 -0.24364550 -0.34426981 -1.9872910 1.64302120

9 0.15893717 -1.12298826 -1.1821257 0.05913740

10 0.14496475 -0.99857142 -1.2100705 0.21149908

11 0.34222975 -0.87656742 -0.8155405 -0.06102693

12 0.25219145 -0.03304643 -0.9956171 0.96257066

13 0.03532625 -0.49529863 -1.4293475 0.93404886

14 0.36410633 0.12453660 -0.7717873 0.89632394

15 0.29988593 0.09678258 -0.9002281 0.99701073

16 0.19837037 0.38422270 -1.1032593 1.48748196

17 0.07807041 -0.58143038 -1.3438592 0.76242880

18 0.07935690 -0.34324576 -1.3412862 0.99804044

19 0.57000953 -0.39054205 -0.3599809 -0.03056111

20 0.34523284 -0.67548411 -0.8095343 0.13405021

While it is helpful to see the model error for every observation, we will need to aggregate them in some way to form an overall measure of the total amount of error for this model. Some alternatives for aggregating these individual errors could be using

- the sum of the residuals (SR),

- the sum of the absolute value of residuals (SAR), or

- the sum of squared residuals (SSR)

Among these alternatives, (a) is not a helpful aggregation as the positive and negative residuals will cancel each other, and (a) may misrepresent the total amount of error for all observations. Both (b) and (c) are plausible alternatives and can be used. On the other hand, (b) is less desirable because the absolute values are mathematically more challenging to deal with (ask a calculus professor!). So, (c) seems to be a good way of aggregating the total amount of error, and it is mathematically easier to work with. We can show (c) in a mathematical notation as the following.

\[SSR = \sum_{i=1}^{N}(Y_{(i)} - (\beta_0+\beta_1X_{(i)}))^2\] \[SSR = \sum_{i=1}^{N}(Y_{(i)} - \hat{Y_{(i)}})^2\] \[SSR = \sum_{i=1}^{N}\epsilon_{(i)}^2\]

For our model, the sum of squared residuals would be 17.767.

sum(d$error^2)[1] 17.76657Now, how do we know that the set of coefficients we guesstimate, {\(\beta_0,\beta_1\)} = {-1.5,2}, is a good model? Is there any other set of coefficients that would provide less error than this model? The only way of knowing this is to try a bunch of different models and see if we can find a better one that gives us better predictions (smaller residuals). But, there are infinite pairs of {\(\beta_0,\beta_1\)} coefficients, so which ones should we try?

Below, I will do a quick exploration. For instance, suppose the potential range for my intercept (\(\beta_0\)) is from -10 to 10. I will consider every single possible value from -10 t 10 with increments of .1. Also, suppose the potential range for my slope (\(\beta_1\)) is from -5 to 5. I will consider every single possible value from -5 to 5 with increments of .01. Given that every single combination of \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\) indicates a different model, these settings suggest a total of 201,201 models to explore. If you are crazy enough, you can try every single model and compute the SSR. Then, we can plot them in a 3D by putting \(\beta_0\) on the X-axis, \(\beta_1\) on the Y-axis, and SSR on the Z-axis. Check the plot below and tell me if you can explore and find the minimum of this surface.